Multicolored lights flash in synch to the beat in a karaoke lounge. A bed remains unmade. Assorted dumbbell weights lie scattered on a gym floor. In his installation Borders re/make Bodies: Chiang Mai Ethnography (2017–ongoing), Samak Kosem addresses the sexual ambiguity of Burmese men in a diasporic, Thai framework. Leading double lives as masseurs and sex workers, these illegal immigrants in Chiang Mai live in the margins, dealing with multiple forms of oppression and inequality. The title of this exhibition at Richard Koh Projects, “Phantoms and Aliens,” isn’t merely a reference to a favorite genre; it’s a unifying concept highlighting “The Invisible Other,” which reverberates through the gallery’s spaces in Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, and Singapore.

In the final chapter, Kosem’s video I don’t have an ID but I have my Body (2020) shows young Shan men playing football or working out in the gym, demonstrating “they are concerned with the need to improve their bodies and to prove their masculinity.” Pointing also to the idea of prostitution as performance, Kosem’s rumpled sheets and massage bed, among other images, convey the process of cozying up to other men, forcing an orgasm every time, and then filling in a worksheet — followed by further desecrations of the body with more clients and more sexual demands.

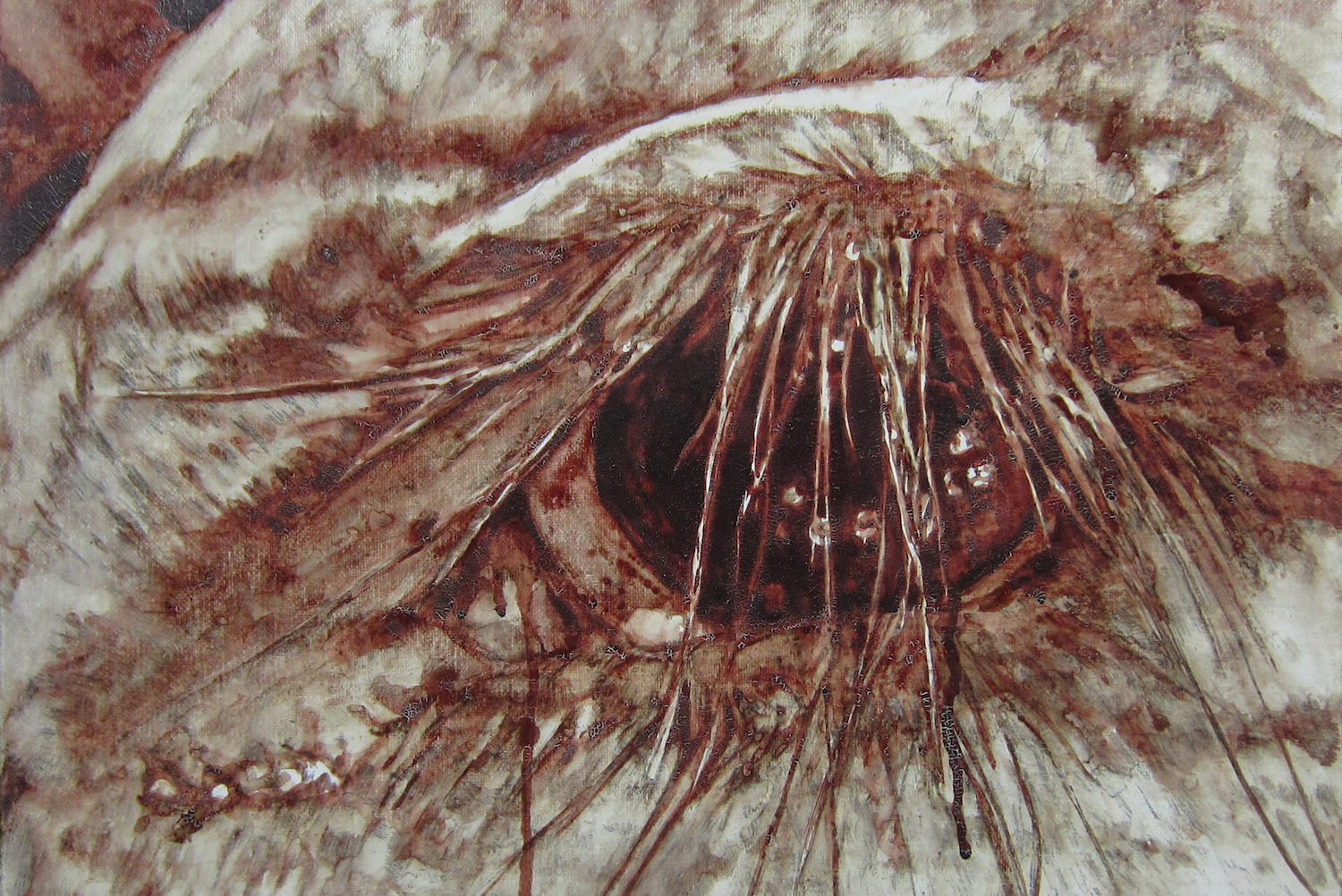

Providing a striking and ironic juxtaposition to the flesh trade is Nguyen Van Du’s paintings of an abattoir smeared with the blood from slaughtered cattle. In his 22 Layers of Cow Blood (2019), Nguyen covered his large canvas with cow blood by marking, dripping, bleeding, and spotting, his color palette alternating between blood red, sangria, black, and brown. On the other hand, Cow’s Eyes #2 (2020) shows a close-up of the animal’s soulful eyes with their long lashes, suggesting the phrase “eyes are the windows to the soul.” These images can be seen as representing the invisible other’s cry of awe and anger at his tragic self-awareness and helplessness.

Scattered around the floor of the Singapore gallery are old galvanized pots of various sizes, some in tipsy stacks, others appearing to slowly warp and bulge over time. The assemblage may convey a meager and even trivial kind of beauty, but the naturalness and humanity of the form arouses strong feelings. Here Yangon-based artist Khin Thethtar Latt’s installation Pot Pagoda (2019) evokes the real and imagined place of Mrauk Oo, a city in the conflict-ridden Rakhine State in Myanmar. Symbolizing the water of life, the viewer’s experience of these pots is complex and moving.

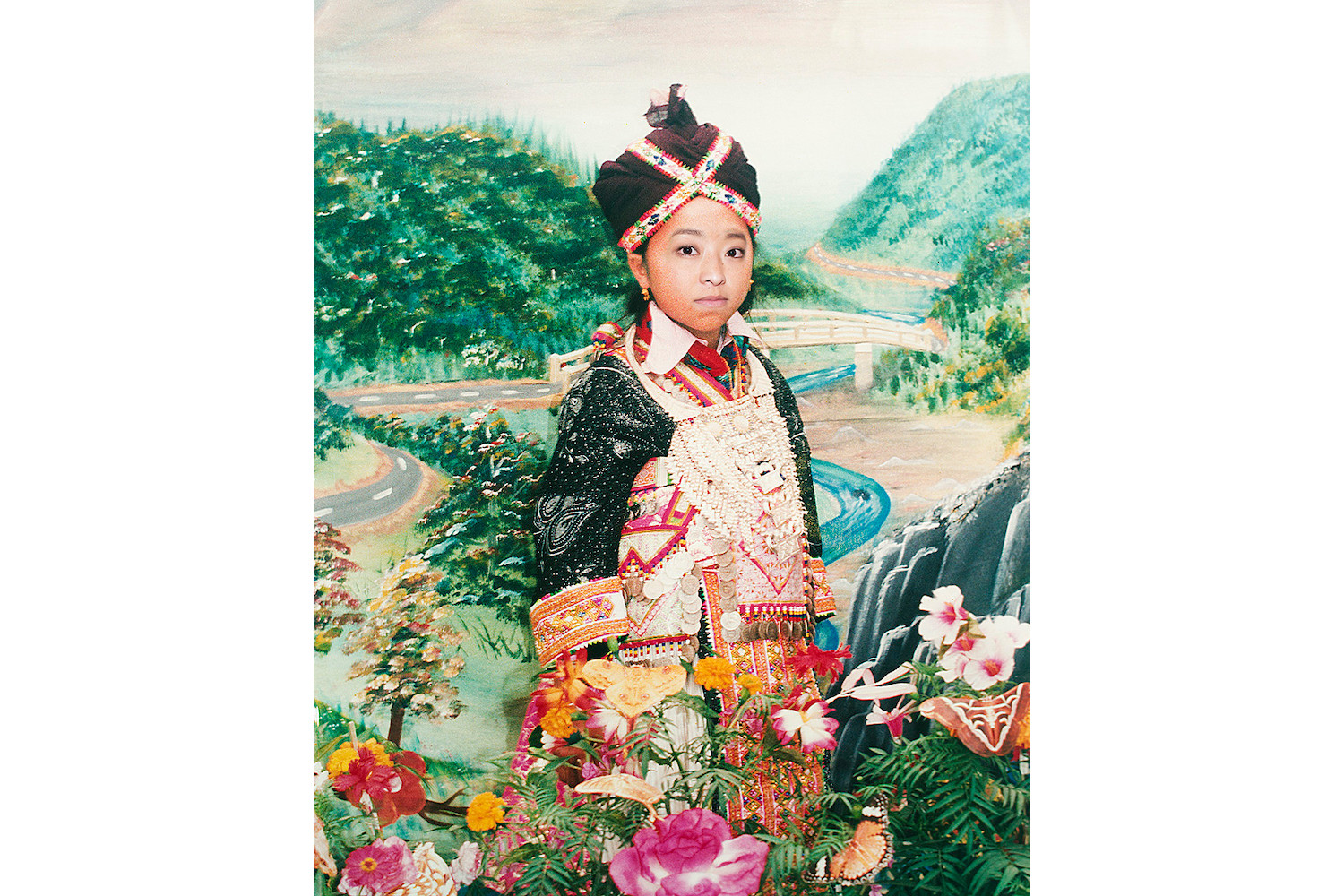

Photographic works by Pao Houa Her explore mythmaking and memory as she reflects on her Hmong family’s experiences of immigration to the United States from Laos. My Grandfather Turned into a Tiger – Jungle Tiger (2017) is a suitable starting point, if only because it reverberates with the mythology of the tiger in Southeast Asia. Featuring a handsome tiger with beautiful stripped fur lying on grass, her 3-D lenticular image depicts her late grandfather as a tiger, expressing something of the spirituality or life force of the dead. Her’s narratives comment on the ambiguous relationship between men and beasts, civilization and nature, those who are controlled and those in power. The exhibition explores the spaces that difference makes — the potentially nurturing places of resistance and struggle, and what they can mean for us.